If you spend much time reading the discourse around nuclear power, you will probably have heard the line, “Nuclear has no natural constituency”. The logic behind this statement is that the nuclear industry is small due to its density. This means few companies make money off it, few workers work for it, and so it does not have much political clout. It is capable of producing very cheap power under the right political circumstances, but that benefit is widespread and diffuse. It benefits all of society rather than a narrow focused group, hence, it has no natural constituency. Meanwhile it has many natural enemies with very focused agendas. The coal industry, the natural gas industry, and the oil industry all do not like it very much. All 3 have large workforces as well. Geopolitical rival nations also are not fans. All these constituencies will happily finance opposition wherever possible.

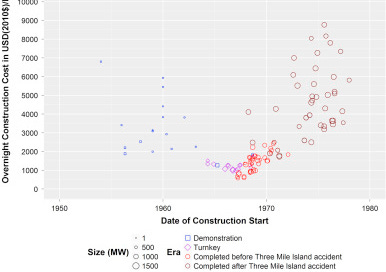

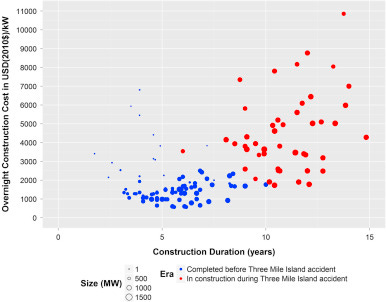

Of course, in a functioning democracy, there is one natural constituency that does have an interest in widespread gains…politicians. Widespread increases in societal well being through economic growth and lower pollution will always help politicians get reelected. Historically this was the case as well, as large build outs of nuclear power have been completed in various countries over time. The US completed a substantial build out during the 1970s and early 1980s consisting of more than 100 reactors. The reactors where construction began in the late 1960s managed to be built very cheaply and on time, while those started in the 1970s were dramatically more expensive.

What changed? The politics of course! The politicians, who benefited from increases in living standards very suddenly changed their tune on nuclear power from very supportive to placing increasing regulation on it. Why would they do that?

There is some interesting research that has been conducted by James G. D'Angelo which might shed some light on why this political change occurred. He is focused more on why inequality also took off during the same period as nuclear plants became more expensive. To paraphrase his findings:

Prior to the early 1970s congressional committees in the US were private affairs that lobbyists were not allowed to attend. Congressional votes were also frequently done by hand count, frequently without recording individual congressperson’s votes. This meant that lobbying interests could be easily dissuaded, since any money given to a congressperson could easily be taken without a desired result returned. This changed in the early 1970s with congressional vote reform. Suddenly everything was recorded and committee meetings made public. Now interested lobbies could see exactly what the representatives they gave money to did. Vote buying became possible and inequality began rising in a sustained way. Congress began not caring at all about what voters thought while economic elites began to get their way much more consistently.

I think this change likely had a lot to do with why the politicians changed their tune on nuclear power. Suddenly very noisy and well funded anti-nuclear groups could apply a lot more pressure to the politicians. Defending nuclear because it was causing broad based improvements in living standards became irrelevant, since those gains would be slow to materialize, but the short term political and financial bashing any politician would receive for doing so might lose them an election immediately. Committees responsible for regulating nuclear energy were made prone to interference by other interests. This meant regulatory ratchet mechanisms put in place causing exploding costs, gridlock for long term waste storage, and the reduction of government support for nuclear research.

Nuclear did have a natural constituency, but it looks like sunshine laws probably killed it.